‘It’s the great disappointment of architecture that most architects waste their time just designing buildings.’ Young and Candy, 2019.

The anthropocentric mass that is the concern of practitioners in the built environment is at the heart of the current climate crisis. It is both the urgency with which we need to act to repair Earth’s natural systems and the short-term perspective of architecture and design that led me to examine my own practice and my role as a designer in the construction industry.

Through my practice at Arup and my design work, I wanted to explore the role of critical futures studies and design futures in the context of the built environment. This hopefully becomes an invitation for more practitioners in the field of both futures and architecture to co-create our collective futures.

In this piece I also reflect on how we can use speculation and alternative futures to allow built environment professionals to use futures methods and tools to embed futures thinking into their practice.

Can we make space for futures architecture?

As a designer and having trained as an architect, I was concerned with how the tools and ways of working I had at my disposal allowed me to broaden my practice to include imagining and speculating on more hopeful climate futures. When I set up a design studio at Arup’s foresight team, I wanted to start a dialogue between architecture and futures, and the following musings hopefully bring a useful framework for folks in this space to reflect on their own practice, and perhaps even relate to similar experiences or hopes they have for their own work.

I wanted to explore how the broad set of practices of design futures can be brought to bear on the built environment using ideas of play, experimentation, intuition and feeling to engage professionals and the industry in the material quality of alternative futures and regenerative futures. Importantly, I will reflect on how my work in design futures has allowed me to reflexively challenge my training and practice as an architect.

Through my own journey between architecture and futures field, I realised that the concepts and frameworks I discuss in this essay were already available to me through my education and practice but were not considered part of the role of an architect.

I believe that futures methodologies can be ushered in as part of the design process within the built environment, and that speculations on alternative futures should become a critical tool to examine how the human-made interventions can be reimagined in the face of climate change.

I found two aspects of my work most inspiring:

Imagining futures in the built environment: Advocating the expansion of the architect’s duties beyond “just designing buildings” but also modelling the future(s).

Future films as imagination tools: Using film as mediator for delivering ideas on building futures and introducing stakeholders to futures studies and its tools.

They both relate to my thinking about diversifying the futures field, supporting a shift to architects reimagining the built world as actors well-placed to enact critical futures approach.

Imagining futures in the built environment

One of the reasons why I became enthralled with architecture was the ability I had to create new stories for every space and building I designed, imagining what new narratives they will provide for its occupants, and what will become of them in time. While architects are concerned predominantly with the ‘now’ and creating physical representations of their ideas, I also understood that the climate crisis should push architects to imagine alternative futures for our cities, where nature and the built world are in a symbiotic relationship.

I couldn’t reconcile the immediate impact I had by erecting a structure on its environment, and that I did not consider longer time horizons. While designing the materiality, concept and structure of a building, I did not seek to understand how the building’s narrative and material quality fits in with preferred pathways for our planet. This did not make sense to me since buildings are artefacts which remain for generations, yet there are no frameworks for considering their futures as well as their presents.

Young’s position that ‘it’s the great disappointment of architecture that most architects waste their time just designing buildings’ (Young and Candy, 2019) really resonates with me as an architect and a practitioner in critical futures field.

I refer to myself as an architect, and I advocate for the expansion of our duties beyond ‘just designing buildings’, but also modelling the futures. This should be a reciprocal act where the futures practice critically examines the intent of any design, and the design seeks to respond to the brief created by that enquiry.

Working at scale

As a futures practitioner in the construction industry, I apply scale as a framework or a reference point to link futures methodologies and the design of the built world.

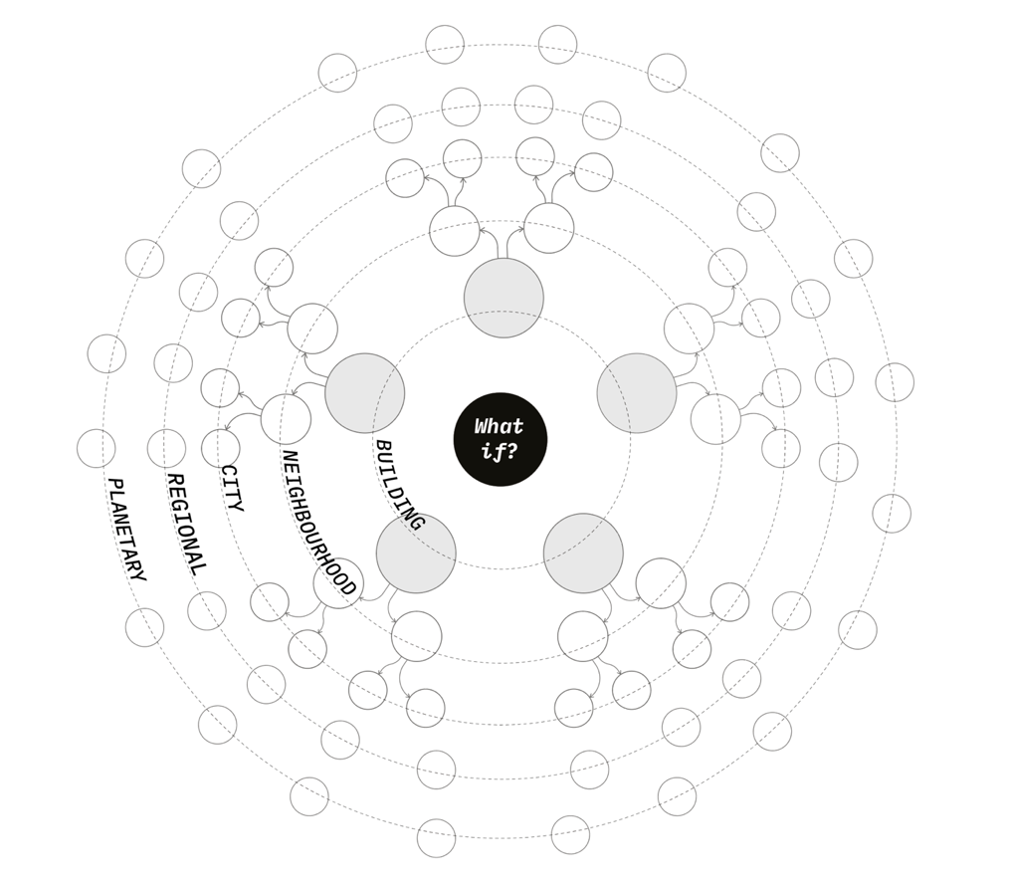

An example of a framing I find most helpful when imagining futures with a ‘what if?’ question for the built environment is a scalar futures wheel (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Futures wheel with scales

Note. Based on Futures wheel by by Jerome C. Glenn (1971).

This approach allows to create narratives about the future which consider how a building in the future might be embedded in a neighbourhood or a region; how its context across social, political, and environmental landscapes changes as we zoom in or out. This questions a new layer of its existence – its alternative futures – which are typically not considered as part of the design process.

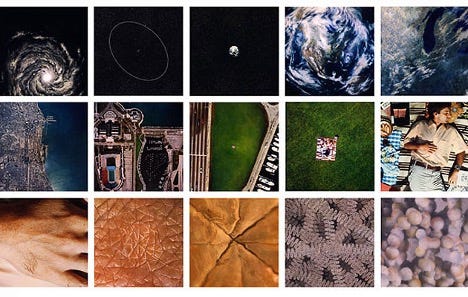

To illustrate nested, intertwined stories of individuals and places, I refer to The Powers of Ten by Charles Eames (Figure 2), a short film (1977) which demonstrates scale through magnitudes.

Figure 2 - Powers of Ten

Note. From Powers of Ten [Image], by Charles Eames, 2013, Icon Eye, Source.

The image zooms out from a couple having a picnic, and every ten seconds we view them ten times further out until we are transported to the outer edges of the universe. This framing unravels complexity, and provides an easily understood point of reference, the size of our body, and uses storytelling to carry the message.

Returning to the idea that architects’ role should go beyond just designing buildings, I wanted to highlight that with every drawing and vision produced by the architect, a story of an alternative world is created, one where the new proposition is brought to life and exists within a newly created context.

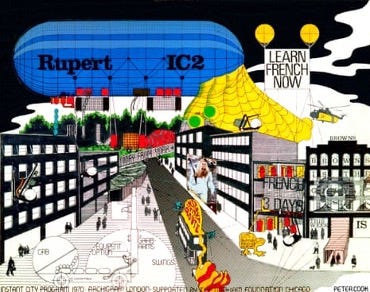

Between 1960-1973, Archigram was a prolific and pioneering visionary group of architects. Their publications depicted speculative proposals like Instant City Airships (Figure 3), inspiring architects to reimagine cities as machines and systems driven by new technologies and modern ways of living (Murphy, 2016).

Figure 3 - Instant City Airships

Note. From Visit to a Small Town [Photograph], by Archigram, 1970, The Guardian, Source.

Archigram’s drawings are a reminder that the futures of buildings should not be foreclosed but explored and reimagined over the course of their existence.

The built world is all around us – we all inhabit spaces, travel across cities, use buildings every day. By enhancing the natural ability for architects to tell stories of other possible worlds, I would like to see the futures practice engage more with the built environment practice, and question what hopeful futures we want to create.

Worldbuilding - Future narratives of our built worlds

The act of critical enquiry into alternative futures is required to rethink our current degenerative systems and propose new pathways into collectively designing futures we want the next generations to inhabit. We need to look far ahead on our horizons to understand how to undo the damage our cities and infrastructure created and align ourselves with the deep planetary timescales we are not used to dealing with.

Worldbuilding is referred to in futures practices as a way of relating possible and plausible scenarios to narratives and storytelling. Leah Zaidi in her essay Worldbuilding in Science Fiction, Foresight and Design, states “Stories are powerful. A story ‘can be a way for humans to feel that we have control over the world. They allow people to see patterns where there is chaos, meaning where there is randomness.’” (Delistraty, 2014)’ (Zaidi, 2019). Architecture is a technically minded profession, and often falls into the problem-solving category, therefore feels natural for me as an architect to extend this muscle and propensity towards solutions to creating narratives around future proposals.

Stuart Candy and Jeff Watson write about “The School of Worldbuilding" (Candy and Watson, 2019) in the context of Bauhaus School of design, which explores new approaches to design today. Their provocation considers storytelling as a tool to reimagine design – how might we design a better world?’ by turning it on its head: how might we world a better design?’ (Candy and Watson, 2019). Through the act of worldbuilding, and through critically approaching new paradigms created within fictional futures, we can suspend disbelief and give rise to a new system or a structure.

‘Worlding a better design’ (Candy and Watson, 2019) is required to reimagine natural and human-made systems and to create alternative futures which work for a thriving planet. Architects creating worlds for future generations should include worldbuilding practices like creative writing or film to invite others to participate in their speculations, and to question how their designs shape futures.

The next chapter will explore how I apply futures in my practice as an architect, and how it allows me to engage stakeholders in my process.

Future films as imagination tools

Film can be a powerful, relatable, and inclusive medium, allowing for an easy entry point to storytelling for stakeholders in the built environment practice. For designers, stepping into the future of the object or building we are designing, and the people we are designing for, is akin to worldbuilding in the futures practice sense. Film can carry a numbers of narrative threads and show scale with ease, whether through a sweeping panoramic shot of a city of through a day in a life of the main character.

My background in architecture allows me to intuitively jump between narrating worlds I create and speculating on what types of objects, buildings, and cities that alternative reality might require.

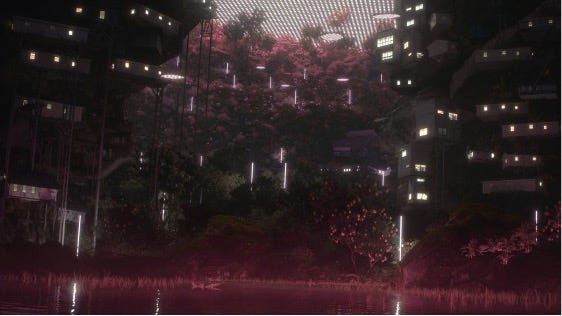

Liam Young’s film Planet City (2021) imagines the world’s population concentrated in one hyper dense city (Figure 4), which uses intense urban farming, energy production and capture, and which collages multiplicity of cultures into a new polytheistic world, creating new typologies of communities.

Figure 4 - Planet City

Note. From Planet city [Film], by Liam Young, 2021, Dezeen, Source

This critical reimagining provokes us to consider how we could radically rethink our consumption models and extractive systems to be more planet-positive, and what compromises we would need to make, perhaps unwillingly, to keep humans alive on the planet.

Storytelling and speculative films are an example of my work which extend the speculation on the plausible and possible futures of the built world into more immersive and discursive space, which help the recontextualise the projects from definite and into more open-ended propositions.

Research and development for the built environment relies on certainties and ‘matters of fact’ (Latour, 2004) which minimise uncertainty for investors, designers, and users. Guarantees around material quality, resilience and usability based on data and scientific method are largely made without inviting consideration of multiple futures. In this way, building projects foreclose alternative futures that fall outside the status quo as a way of mitigating future uncertainty.

In my practice and work with Arup, a leading international design and engineering company, I used speculative film “Abundance” (Figure 5) as a medium through which a range of stakeholders could explore possible and probable regenerative futures and test how the illustration of these futures could aid discussions around preferable futures.

Figure 5 - Harvest festival

Note. From Abundance [Film], by Arup, 2022.

It sparked conversations with my colleagues about the possibility of futures methods and practice offering a range of possible pathways, each with their benefits and trade-offs. The film questioned what a future city would look and sound like, how would our values change in that world and how we would live. These questions may not be at the forefront of how we consider sustainable and regenerative design today, but there is nothing more important to imagine today if we want to create resilient futures for the generations to come.

Through demonstrating a range of possible futures in scenario planning, the built environment can be designed to accommodate the complexities of those emergent worlds and question the inevitability of pre-conceived notions of ‘business as usual’ cities, but rather propose alternative futures that align with planetary health.

As well as using worldbuilding to suggest what cities could look like in a regenerative future, we created film props as pieces of design fiction (Figure 6). They became “objects of inquiry” (Bleecker et al, 2022) and carried their individual narratives which further explored how regenerative design could be woven into our systems and buildings. The term “design fiction” was coined by Julian Bleecker and Bruce Sterling and described ”as a deliberate use of diegetic prototypes to suspend disbelief about change” (Sterling, 2013).

Figure 6 - Autonomous dragonfly

Note. From Abundance [Film], by Arup, 2022.

A speculative practice Superflux uses design fiction objects to create film sets from the future, which construct their proposed 2050 Mitigation of Shock, creating a hopeful scenario for a future world disrupted by climate change.

These new imaginaries present the audience a critique of the current degenerative systems, and proposed alternative, regenerative ways in which we could design at all scales. Physical objects presented as tangible artefacts resonate with the built environment practitioners and became a useful lens to discuss preferable futures. They also become practical design research tools, critiquing the status quo, asking stakeholders involved in the design process to reflect on the type of futures the intended designs are deployed into, therefore allowing futures thinking into their work.

The recent emergence of more radical approaches to imagining our futures should encourage architects to engage in futures practices to the benefit of our collective building of more resilient and abundant spaces.

Bringing our imagination back to Earth, literally.

We can and should use futures tools when creating the built environment, especially within the architectural profession.

The transition to a regenerative future demands an upending of the status quo, attitudes to design and the built environment. It must embrace a variety of perspectives and uncertainty to meet the needs of resilience and adaptability we will need to reorient the relationship between people, the built environment, and the natural world to have mutually reinforcing systems (Pawlyn, 2021). This calls for futures practitioners to become more involved in co-creating new imaginaries for the built worlds and to broaden the field of futures studies to include practice-based practitioners.

Design futures, speculative design and critical futures arguably explore ‘matters of concern’ (Latour, 2004). That is, issues that are subjective and vague, based on feeling, belief, and intuition and in doing so embrace and consider a diversity of perspectives and futures as well as the inherent uncertainty of life in climate change. Donna Haraway describes this discomfort as “sitting with the trouble” (Haraway, 2016) and describes how we relate to matters of doing things in systems and collectively. This co-creating approach is also rooted in architectural practice but should be looked at through a futures lens to understand the worlds which are created.

Through my own journey between architecture and futures field, I realised that the futures concepts and frameworks I discuss in this essay were already available to me through my education and practice. However, I need to reinvent them and create a new set of futures tools fit for architectural profession which designs for a more thriving planet in the coming decades.

Current built environment practices fail to serve nature and all living things. The construction industry must collate ideas from vernacular typologies, indigenous communities, and biomimetic designs and creative speculative films, buildings, and community projects which can emerge as powerful mediums for conveying future narratives and inspiring change.

There is nothing more urgent today than dealing with the climate crisis and this essay is an invitation to both futures practitioners and the built environment practitioners to collectively reimagine the current status quo and slowly heal the anthropocentric mass using new narratives.

Loved loved loved reading this, shared to me by a colleague - thank you for your work! Are you still with Arup ?